Client Memo: Sometimes It’s What You Don’t Own That Matters

Feb 10, 2026Not long ago, a client emailed me asking if we had any exposure to business development companies (BDCs) in his portfolio. He was asking because he clearly noticed media headlines about steep declines in software stocks and BDCs. The catalyst was the theory that AI is going to displace the need for certain software companies.

Software stocks have plunged on this narrative. The BDCs act as a financing mechanism (a “shadow bank”), lending these companies capital to operate. The BDCs are being clobbered because the market is theorizing that the loans will go bad.

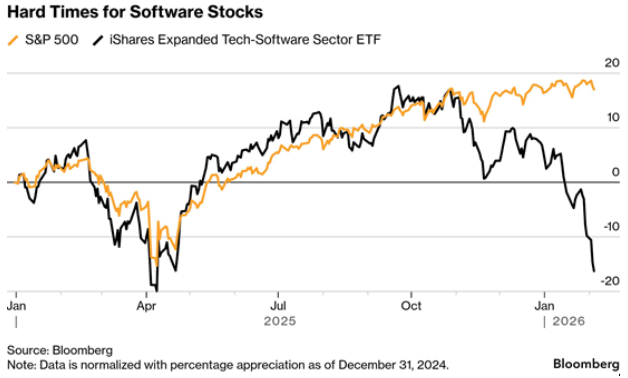

The iShares Expanded Tech-Software Sector ETF fell 16% in January 2026 alone, pushing the software sector into bear market territory.

BDCs are a form of private credit, something our industry has been jumping into without a second thought over the last ten years. Private credit has grown from just $200B in 2015 to nearly $3.5T by the end of 2025, according to some estimates.

Private credit is simply direct lending by non-bank entities. Think of someone setting up a pool of capital to which they lend out that capital to smaller companies that are looking for loans. Those loans are not traded publicly like a typical corporate bond that we hold in client portfolios.

For many investors watching these declines, the instinct is to wonder: "What should I be buying right now?" But there's an equally important question that often gets overlooked: "What should I not own?"

The Power of Avoidance

Warren Buffett famously said, "The first rule of investing is don't lose money. The second rule is don't forget the first rule." While that might sound like folksy wisdom, there's real substance behind it. In portfolio management, avoiding significant losses is often more valuable than chasing big gains.

Here's why: If you lose 50% on an investment, you need a 100% gain just to get back to even. The math of losses is brutal. A portfolio that avoids major drawdowns doesn't need to work nearly as hard to generate strong long-term returns.

This is where disciplined portfolio construction comes in. Sometimes the most important decision isn't what you buy. It's what you deliberately choose to exclude.

What Happened with Software Stocks and BDCs?

Let's walk through what actually happened, because it illustrates this principle perfectly.

The Software Sector Reckoning

For years, enterprise software companies were seen as safe, predictable growth stories. Companies like ServiceNow, Salesforce, and Workday built businesses around recurring subscription revenue- the holy grail of business models. Investors loved the visibility and the steady growth.

But in late 2025 and early 2026, a narrative shift occurred. The rise of AI tools, particularly AI agents capable of automating tasks that previously required expensive software licenses, created existential questions. What if AI doesn't just make software more efficient but actually replaces entire categories of software? What if "seat-based" pricing models collapse because AI agents can do the work of ten employees?

Suddenly, solid earnings reports weren't enough. ServiceNow beat expectations but still fell 13%. The market wasn't buying in the past- it was pricing uncertainty about the future.

The BDC Contagion Effect

BDCs operate in the private credit space, lending primarily to small and mid-sized companies. Many of these companies are in- you guessed it -the software sector. As software stocks cratered, investors began asking uncomfortable questions about the loan portfolios inside BDCs.

If software companies are facing an AI-driven disruption, what does that mean for their ability to service debt? Are we looking at rising defaults? Will private credit valuations hold up?

The result was a rapid sell-off. BDCs with heavy software exposure got hit hardest, but even those with more diversified portfolios saw declines as investors fled the entire category.

What We Didn't Own—And Why It Matters

This brings us to the most important part of the discussion. In our portfolios, we've maintained limited to zero exposure to both enterprise software stocks and BDCs for quite some time. This wasn't because we predicted the exact timing or mechanism of these declines. It was because we identified structural risks that didn't adequately compensate us for the potential downside.

BDCs present a unique set of challenges. On the surface, they look attractive- high dividend yields (often 8% to 12%), exposure to private credit, and the promise of steady income.

But dig deeper and you find layers of complexity:

- Leverage risk: BDCs use substantial leverage to amplify returns. This works great when credit conditions are stable, but it magnifies losses when defaults rise.

- Valuation opacity: Unlike public stocks, the underlying loans in BDC portfolios are often marked subjectively. You're trusting management's assessment of what those loans are worth.

- Sector concentration: Many BDCs have significant exposure to specific sectors. When those sectors struggle, the entire BDC can face stress.

- Liquidity risk: In a stress scenario, BDCs may struggle to sell illiquid loans, making it harder to meet redemptions or manage capital.

The high dividend yields weren't compensation for normal market risk- they were compensation for these structural vulnerabilities. When we analyzed the risk-adjusted returns, BDCs didn't make the cut.

What we're describing here is a form of "negative screening"- the deliberate exclusion of certain investments from a portfolio.

“Negative Screening” as Risk Management

Negative screening is often associated with values-based investing (avoiding tobacco, weapons, etc.), but it's equally powerful as a risk management tool. By systematically excluding investments with unfavorable risk-reward profiles, you reduce the probability of catastrophic losses.

Once we identify an unfavorable risk-reward, we exclude it, even if it's popular, even if it's been working recently, even if other investors are chasing it. Typically, where the money is flowing is often a good indication of what investors and advisors are being sold – and that typically is a function of selling good past performance.

When crowds all chase the same things and money pours into a sector, it increases the price of those assets and reduces future returns. It also tends to bring in unscrupulous selling practices and eliminate covenants and other safeguards.

Avoiding these ‘hot’ areas is typically good practice. This discipline is what protects portfolios during market dislocations.

The Takeaway

Portfolio management isn't just about finding winners. It's about systematically avoiding losers- or more precisely, avoiding situations where you're not being compensated for the risks you're taking.

The recent declines in software stocks and BDCs serve as a timely reminder of this principle. By choosing not to own BDCs or over own software stocks, we avoided the losses that came when those risks materialized.

This is the unglamorous, often invisible work of portfolio management. It doesn't generate headlines or cocktail party stories about the hot stock you picked. But over decades, it's what separates strong long-term performance from disappointing results.

Sometimes it really is more about what you don’t own.

As always, we appreciate the trust you place in us and are here to answer any questions you may have.

Sincerely,

Mark J. Asaro, CFA

Noble Wealth Management